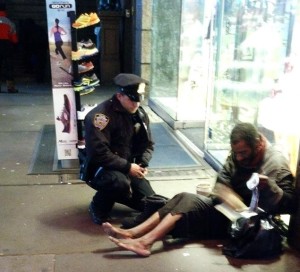

For a few weeks in 2012, this picture was everywhere: A New York City police officer offering a pair of boots to homeless man. When I saw this photo, I was moved to tears by this officer’s love and humility.

“What Would Jesus Do?” This.

When I looked closely at the picture I was shocked. I knew that homeless, shoeless man. I had seen him six years earlier, walking up Fifth Avenue in the freezing cold, without shoes or socks. Unlike that cop, I didn’t go and buy him shoes. I didn’t kneel to help him put them on. In Matthew’s gospel, Jesus says, “Just as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to me.” And on a bitter cold day, right in front of beautiful Christmas decorations celebrating the birth of the Savior, I saw Christ suffering and kept on walking.

I wasn’t indifferent. I was just paralyzed.

The sight of him began a frantic dialogue in my head: “I have to do something. Is it safe to approach him? Should I buy him shoes? How would I know what size? Maybe I could bring him into Lord and Taylor. Would they even let me in with him? Would he just turn around and sell the shoes and use the money for God knows what?” As the questions swirled in my head, I kept walking in the opposite direction.

I was shaken for days afterward. The sight of a homeless person wasn’t new to me — I’ve lived in the New York area most of my life, including the “bad-old days” of the 70s and 80s, when it seemed that every subway station and street corner was a great black hole of human need. I was taught to look away, hold tight to my purse and keep moving. But this day was different. I wanted to help, but didn’t know where to begin. I wanted to do something, but felt utterly impotent.

This is the flip side of the Mighty Mouse delusion I wrote about in my last post. Instead of feeling all-powerful to save, we can feel weak and small and useless. Just this morning, I looked at pictures of refugees emerging from the Aegean Sea with that haunted look in their eyes, and I thought —I am just one person, far away, with no useful expertise to offer. Could I be more useless?

Instead of rushing in with fantasies of saving the day, we can let the enormity, the complexity or the intractability of the problem render us immobile. The flip side of thinking ourselves more powerful than we are is believing we have no power at all. Each is a serious misunderstanding of what God asks of us.

Sometimes we think that in asking us to feed the hungry, God expects us to eradicate hunger. We think that in asking us to clothe the naked, God is expecting us to eliminate poverty. Not so. When Jesus says, “The poor you will have with you always,” it is a sobering reminder that we live in a broken world that only the Second Coming will completely heal. Still, this isn’t an excused absence from doing social justice. We are still called to love, clothe, feed, visit and bear one another’s burdens. But we do so knowing that the ultimate, complete restoration of God’s good creation is yet to come.

God is in charge of eternity. We are responsible for today. Regardless of the final outcome, every act of service and love is holy and sufficient in and of itself. Ironically, several weeks after the policeman bought him new boots, that same homeless man was spotted, barefoot once again. The cynics said, “See, he probably sold those boots and bought booze. That cop was a sucker.” Maybe so.

Loving and caring for God’s people can be a messy business. It isn’t always clear what to do, when to do it, or how. There’s no guarantee that you won’t be taken advantage of, or that what you do will really help. But God only asks us to act, and to leave the outcome to Him.

We are not all-powerful. We are not powerless.

The life of faith is lived in the tension between these two poles. St. Ignatius put it this way: “Act as if everything depends on you. Trust as if everything depends on God.”