“You sure do ask a lot of questions for someone from New Jersey.”

Saturday Night Live fans of a certain age will recognize Rosanne Rosannadanna’s response to all those letters from Mr. Richard Feder of Ft. Lee, New Jersey. Like the fictional Mr. Feder; I sure do ask a lot of questions.

It’s like part of my brain is still two years old, constantly asking Why? Why not? Where? When? Who? How? What if…

When I was in the corporate world, this held me in good stead. A client once told me, “At the beginning of a project, I always know that sooner or later I’ll get The Phone Call From Laura. You know, the one where you ask lots of questions, usually questions that no one had thought of. Or worse, questions that exposed the weakness in the product design, marketing strategy or communications plan.” My litany of questions helped me craft the right message for the audience, and sometimes helped my clients rethink their products and strategies.

On the homefront, my husband will tell you that any story he tells will spawn a series of questions: “Did she say why?” “Did you ask if she needed …?” “What did he say” “What did you eat” “What was she wearing?” “Do they need us to call/go/do/something?” Every one of his sentences seems to give birth to three of my questions. Did I mention the man is a saint?

I ask God lots of questions, too. There are the Big Questions that are cosmically important, the ones every one asks: “Why is there evil and suffering”. “How do I forgive?” “What is your purpose for my life?” Then there are less weighty ones, really born more of curiosity than theological moment, like what was Jesus like as a child, do dogs go to heaven and will I have this body in the resurrection or dare I hope for a better one?

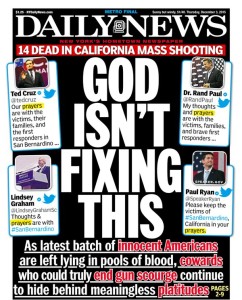

Here’s the weird thing. For someone so inquisitive, I’m oddly uncurious about myself. Days come and go and I do what I do, say what I say, feel what I feel, and don’t really stop and ask any of the questions I’d so readily pepper someone else with: “Why did you do that? How did you feel when that happened? Could you have done that better/different/not at all?” I don’t examine my day to see where God was, where God wasn’t, where I stumbled, where I soared. Of course, sometimes, God’s presence or absence is very obvious, in a burning bush sort of way. When I witness a miraculous healing, there’s no need to look very hard for God; there He is, plain as day. When I see cruelty or violence, I don’t need to do an exhaustive search to know that God isn’t in it.

But often, God’s presence is hiding where I don’t think to look.

Often my motivations are a mystery to me and my actions are a disappointment. I often find myself baffled by the disconnect between my intentions and my actions. But at least I’m in good company — St. Paul tells us he had the same frustrations:

“For I do not do the good I want,

but the evil I do not want is what I keep on doing.”

Romans 7:19

And so, this Lent, I’ve decided to turn the questions on myself, using an ancient spiritual discipline called the Prayer of Examen. In his delightful book, The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything, James Martin says, “God is always inviting us to encounter the transcendent in the every day. The key is noticing.”

And the key to noticing is to take stock, performing a daily, prayerful spiritual inventory. The Examen begins with gratitude for what the day has brought. It continues by asking the Holy Spirit to come and shine a light on the day past. We ask the Spirit to show us where we have honored God and where we have failed Him. We ask for forgiveness where it is needed. The point is to help us see ourselves as God sees us, rejoicing where He rejoices, to feel grief over where we have grieved Him, and to accept his grace and forgiveness.

I know that doing this under the guidance of the Holy Spirit is crucial, particularly when it comes to acknowledging where I have fallen short. Often, I think I know perfectly well what I need to repent.

But there’s a weird Catch-22 of the spiritual life: my consciousness of sin is clouded by my sinful nature.

How do I repent what I’m not even aware of? I need the power of the Holy Spirit to help me see clearly what needs to be confessed and forgiven. I need the power of the Holy Spirit to reassure me that God knows that I am better than my worst moments, more than my sins. God doesn’t want my confession to gather evidence for my prosecution; he wants it to exonerate me, to make me whole. I can feel safe making this searching and fearless inventory because I know God rejoices over every prodigal who wants to come home.

If you’d like to join me on this road paved with questions, here is one version of the Examen:

(For a wealth of resources on the Prayer of Examen and Ignatian spirituality, I recommend visiting Ignatian Spirituality.)