or How I Wound up Building a Shack

I’ve been a writer most of my life. When I was in elementary school, I wrote in a little red diary with a gold lock and key, then graduated to spiral bound notebooks full of poetry and teenage angst. I wrote in marble composition books, in leather-bound journals and on manual typewriters whose keys would stick and tire my hands.

Eventually, I became a corporate wordsmith-for-hire and I wrote what others wanted — their message, their schedule, their purposes. And I wrote what I wanted less and less. The thing was, at the end of a long workday, I just didn’t have any more words left in me.

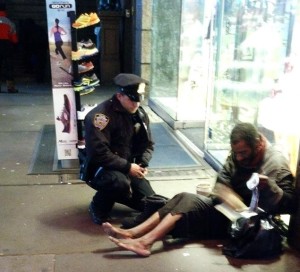

Last year I decided to do what I had long dreamed of: write in my own voice. And so, three months ago, I began a construction project. I dreamed of building something beautiful, something that would use my life and my gifts to draw people closer to God. I envisioned using my words to invite people into a warm and welcoming cottage where we could sit by the fire and share the joys and challenges of following Jesus.

I tackled it like any of the other product launches I’ve worked on over the years. I took care of the infrastructure (procuring domain names, setting up the website, etc.). I devised a marketing plan. I tried to make the best product I could and deliver it regularly. I set benchmarks to measure success — Likes, followers, retweets, subscribers, comments.

I found joy in writing what is in my heart. With every post, I kept a careful eye on those “success” benchmarks. What a joy to receive praise! Every positive comment makes me giddy. Every new subscriber buoys my spirits. Every new follower makes me feel like I matter. It’s been over a year since I left my last job, a year of discernment in which I often felt uneasy and adrift. The praise and Likes and Favorites quieted that unease and gave me direction. “I have a purpose. I have value. Yes, this is who I am now.”

Wait. What?

I have always looked to external measures and rewards to tell me who I am. I was the kid who looked forward to report card day. A gold star told me I was a good girl, worthy of love and attention. To this day, when I walk into a room, I quickly get the lay of the land: Am I the thinnest woman here? the best dressed? the smartest, wittiest, most organized, the holiest? (By the way, the answer to all of these is usually “no”. Still, that’s OK. I can exhale and get on with it, just knowing where I fit in the pack. I guess in that respect, I’m temperamentally more dog than cat).

Every A, every gold star, every comparison I ever made told me

who I was and what I was worth

And I was doing it again. Without realizing it, I had gone from wanting God to use me to using God to get those gold stars that would make me feel important and worthy. I was amazed at how easily the line is crossed between doing something for God’s glory and doing it for my own. It stopped me dead in my tracks. What do I do now?

I stopped writing and started reading. A book about Ignatian spirituality, Eugene Peterson’s A Long Obedience in the Same Direction, and one about Islam. Most importantly, I started my “Bible in a Year” reading program, (only a few weeks late!) because I knew that my words needed to be undergirded by and subject to The Word. And that is where I read this:

If God doesn’t build the house,

the builders only build shacks.

(Psalm 127, The Message)

I wanted to build a beautiful cottage and instead was well on my way to building a shack. No cozy chairs by a warm fire, just made for conversation. No, what I and my hunger for the world’s gold stars had built was just a bare bones, barely adequate shelter.

That Psalm reminded me that God must be the architect; I am just the construction worker. I bring him what I have: my words, my heart, my fingers on the keyboard. I ask Him to remind me, as many times as necessary, of who I am in Him and what I am worth to Him. I bring my repentance when I forget. I ask Him to be my divine “blind spot warning system” that lets me know when I need to make a quick course correction. And I work to expand the audience for the message he entrusts me with, remembering that all those Likes, Follows and Favorites belong ultimately to Him.

Mother Theresa said, “I do not pray for success. I ask for faithfulness.” Amen and amen.