In this life, there are headliners and there are backup singers. The headliners get the fame and the spotlight and the melody. Then there are those who stand in the shadows, off to the side, adding harmony and rhythm and counterpoint to the song. Their names aren’t on the marquee; they don’t have groupies and they don’t get Grammys. You might think they are pleasant but dispensable window dressing. You’d be wrong. Without backup singers, the music would be flatter, less textured, and less fun. Have a listen to Midnight Train to Georgia and tell me the Pips don’t make that song.

The Bible transcends time and culture, so we shouldn’t be surprised to find stars and supporting players in God’s story, too. In the letter to the Hebrews, we find a lineup of All-Star saints: Noah, Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Jacob, Joseph and Moses, David and Samuel among them. Generations of people have looked to them as exemplars of faith.

There is another list, in another letter. The letter to the Romans concludes with a litany of names — 26 mostly unknown, unheralded saints of the church. (Romans 16:1-16) In exhorting the church to greet these Biblical backup singers, Paul is turning the spotlight towards these saints in the shadows.

He gives just the barest details about them.

“Greet Mary, who has worked very hard among you.”

“Greet Rufus, chosen in the Lord, and greet his mother, a mother to me also.”

“Greet Urbanus, our co-worker in Christ.”

It is largely left to our imagination what they did to merit Paul’s gratitude and love. But we do know this: Paul wanted everyone in Rome to know that these were people worthy of honor and deserving encouragement. He didn’t just pull them aside and say, “Nice job!” He shouted: “Look at these people! They are the saints of the church. They console and nurture. They are the ushers and the bulletin-folders. They keep the lamps filled and the garbage emptied. They bake the bread for the communal supper and wash the dishes afterwards. They pray for you. They are ready to give their money and their lives for the sake of the Gospel.”

I had the privilege of reading their names aloud in worship this week.

I wanted to be sure to say their names clearly and loudly and with love.

I was determined to speak their names boldly because I wanted to turn the spotlight on them, just as Paul had.

Prisca and Aquilla.

Hermes and Hermas.

Andronicus and Junia.

Nereus, Asynchritus

Phlegon, Patrobas and Olympus

I wanted to give them the honor and praise they rarely get, living as they do in the shadow of the Greats.

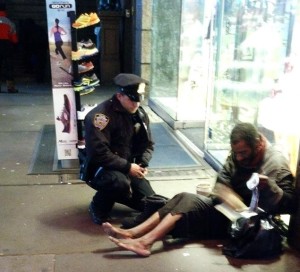

I want us to remember that there are still people like them, in every community. People who quietly and humbly serve in ways most of us don’t even notice. They don’t seek the spotlight and they don’t look for praise. But they do deserve honor and encouragement.

Let’s face it: even when we’re serving out of love, we can get weary. We wonder if what we do matters. Our spirits can flag and our bodies groan. Sometimes a simple “Atta girl!” is balm for the soul. And another thing: acknowledging everyone’s contribution, whether they’re the headliner or just singing the “Wa Wa” in the background, underscores our mutual dependence and need.

So, next time you see Epaenatus straightening the pew cushions, greet him and remind him what an inspiration he’s been.

When you run into Tryphosa and Tryphena at Starbucks, thank them for their quiet servanthood.

Drop a note to Asyncritus or Philologus and tell them how their prayers have blessed the church.

And greet one another with a holy kiss.